This state of genetic integration found in temperate phages such as the lambda (λ), Mu, P1, or N15 is known as prophage, and the bacterial host harboring a prophage is called a lysogen. Although most common in bacteria, lysogeny also occurs in eukaryotes, including plants and animals. The host bacterium lives and reproduces normally in the lysogenic state. At the same time, the bacteriophage exists in a dormant state. However, the prophage is transferred to the daughter cells at each subsequent cell division. A temperate phage can undergo both the lysogenic and lytic cycles. Carrying out the lysogenic process requires the presence of a repressor protein that regulates the expression of the lytic genes. The virus enters the lysogenic cycle in the presence of the repressor protein. In contrast, when the repressor is absent, the virus enters the alternative lytic cycle.

Example of Lysogenic Cycle

What Happens During the Lysogenic Cycle with Steps

Importance of the Lysogenic Cycle

Lytic vs. Lysogenic Cycle

Here are the significant differences between lytic and lysogenic cycles:

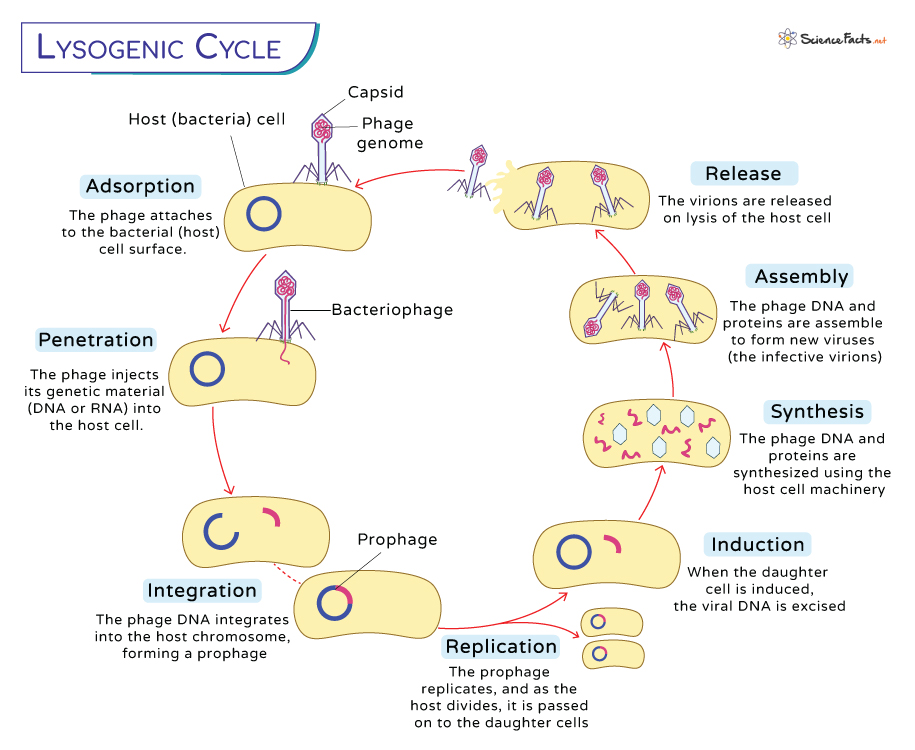

1. Adsorption

This step is similar to the lytic cycle in bacteriophage, where the virus attaches explicitly to the receptors on the bacterial cell surface.

2. Penetration

After successful attachment, the phage injects its DNA into the host bacterial cell. This injection is often facilitated by viral enzymes or proteins that penetrate the cell membrane, allowing the viral DNA to enter the cell’s cytoplasm. On entering the host cell, the phage DNA circularizes.

3. Integration

The circular phage DNA then integrates into the host chromosome using site-specific recombination. It is the hallmark of the lysogenic cycle. Instead of taking immediate control, the viral DNA harmoniously coexists with the host DNA. This integrated state is often referred to as prophage, a key feature distinguishing the lysogenic cycle from the lytic cycle. While integrated into the host genome, the prophage remains inactive and does not produce viral particles.

4. Replication

As the bacterium replicates its DNA, it makes numerous copies of the prophage. When the host cell undergoes cell division, the viral genes are subsequently passed on to the daughter cells and their DNA.

5. Induction

The lysogenic state of the virus may persist for an extended period. Under certain conditions, the phage is triggered to exit the bacterial chromosome and initiate the lytic cycle. It occurs in the presence of environmental stress like ultraviolet radiation or the presence of specific chemical signals.

6. Synthesis, Assembly, and Release

Upon entry into the lytic cycle, the virus utilizes the host cell machinery to synthesize its DNA and proteins required to produce new viruses (virions). The newly synthesized lysogenic phages destroy the host cell. They are released only to participate in a fresh infective cycle, and the process continues. The method of virion release in a lysogenized host is known as budding. At the end of all these stages, the lysogenic host cell can either remain in the inactive latent form until further induction by factors such as UV radiation or may enter the lytic cycle, producing more virus particles. In some cases, lysogenic viruses also benefit their host, increasing environmental stress resistance. Understanding the mechanism of the lysogenic cycle is crucial for developing strategies to control the spread of viral infections and preparing new vaccines and therapies.